The Cycle of Bonding

by Gregory C. Keck and Regina M. Kupecky

There is a common children’s verse that says, “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.” For the abused child, nothing could be further from the truth. While the effects of physical abuse usually heal over time, the psychological insults experienced by the child bring deep, long lasting pain. These wounds fester within, creating ongoing difficulties for both the child and the adoptive family.

Many adoptive children did not experience early childhood trauma, neglect or abuse. The issues these children face are issues common to all children, along with issues related directly to adoption. But for adoptive children who lived through a difficult start, there is a range of developmental diversity tied to the abuse. What is Attachment Disorder? The types of problems that adoptive parents see in their children are most likely the result of breaks in attachment that occur within the first three years. And they are problems that impair, and even cripple, a child’s ability to trust and bond – or attach – to other human beings. Children whose developmental interruptions have resulted in an attachment disorder may exhibit many, or even all, of the following symptoms:

- Superficially engaging and “charming” behavior

- Indiscriminate affection toward strangers

- Lack of affection with parents on their terms (not cuddly)

- Little eye contact with parents (on normal terms)

- Persistent nonsense questions and incessant chatter

- Inappropriate demanding and clingy behavior

- Lying about the obvious

- Stealing

- Destructive behavior to self, to others and to materials things (accident prone).

- Abnormal eating patterns

- No impulse controls (frequently acts hyperactive)

- Lags in learning

- Abnormal speech patterns

- Poor peer relationships

- Lack of cause-and-effect thinking

- Lack of conscience

- Cruelty to animals

- Preoccupation with fire

The pain and heartache the adoptive parents feel cannot be underestimated, nor can the hope that comes with identifying this disorder. From identification comes treatment that can fill in the child’s developmental gaps and allow him or her to grow to maturity. A more completed understanding of each of the traits listed above is a place to start.

The Cycle of Bonding

Even before a child is born, the building blocks of development are being laid. During the critical nine months the child is within his mother’s womb, he must received sufficient nutrition and be free of harmful drugs if he is to develop into a healthy baby. Many of the children who hurt were burn to mothers addicted to drugs and/or alcohol. These children can be viewed as life’s earliest abuse victims, as their systems fail to develop properly. Many times, these children are primed not to attach to a caregiver. With immature neurological systems, they are often hypersensitive to all stimulation. They don’t like light and may perceive any touch as pain. A child in chronic pain, even with the most loving caregiver, may develop attachment disorder as the pain short-circuits his ability to bond.

Sadly, a baby born with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome or with drug-induced problems is most often tended to by a substance-addicted mother, incapable of providing even basic care. His heightened sensitivity and irritability may set him up for further abuse or neglect from his mother as she attempts to parent a baby who is often fussy and upset.

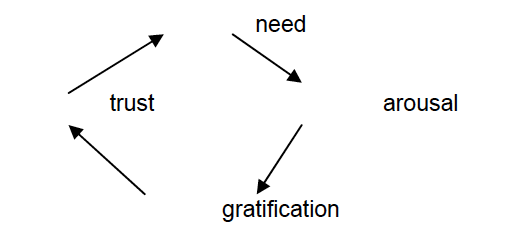

To better understand how abuse and neglect affect a child’s development, it is necessary to understand “normal” development in an infant. Abuse and neglect can interrupt the first and most important developmental process for an infant – the cycle of bonding, as illustrated below.

The Effects of Abust and Neglect

Most professionals who work with and study the process of bonding and attachment agree that a child’s first 18 to 36 months are critical. It is during this period that the infant is exposed – in a healthy situation – to love, nurturing and life-sustaining care. The child learns that if he has a need, someone will gratify that need, and the gratification leads to the development of his trust in others.

Prior to gratification, frustration is heightened. It is during this frustration that the foundation for delaying gratification is laid. This is critical learning with lifelong implications.

Failure to complete and repeat the bonding cycle leads to serious problems in the formation of the child’s personality which, in most cases will have lifelong implications. When the bonding cycle is interrupted problems arise in these areas:

- Social/behavioral development

- Cognitive development

- Emotional development

- Cause-and -effect thinking

- Conscience development

- Reciprocal relationships

- Parenting

- Accepting responsibility

A child born into a dysfunctional environment that features abuse and neglect as the overriding themes will not experience the bonding cycle with any predictability. A complete understanding of each of the traits listed above is a place to start.

Treatment for the Hurt Child: Making if Effective

For therapy to be effective, it must be directly related to the problems that the family and the child are experiencing. Specific problems warrant specific solutions, and boilerplate methods serve no purpose. In must cases, finding the right therapist to point out the right path is the first step toward family harmony.

We continue to hear complaints from adoptive parents that many mental health professionals blame them for their child’s current problems. It is an unfortunate fact that many of those who attempt to provide treatment to adoptive parents with disturbed children know very little about issues related to adoption. This is particularly alarming when we realize that they not only fail to provide effective therapy, but also solidify the child’s existing pathology and complicate subsequent therapeutic efforts. It is not unusual for us to work with families who have seen four to six other mental health professionals without results.

Part of the reason for this ineffectiveness is the fact that while graduate training enables therapists to deal with the neurotic personality, it does not adequately prepare them to deal with individuals who have not yet made it to a developmental level that is complex enough to be capable of being neurotic. Children with developmental delays (social, psychological, cognitive) who have been in traditional therapy tend to be extremely skilled at figuring out the therapist’s goals and style. They effectively assume the role of victim and the therapist responds with sympathy. Rarely does a clinician challenge a ”victim” child, which is precisely what needs to be done when the child is faking it. When the therapist buys into the con, his sympathetic response services to empower the child.

Because many children who have experienced neglect, abuse and abandonment have not yet developed an internalized set of values by which they judge themselves and others, they are not able to receive and experience empathy, nor can they develop insight. They project blame onto others and onto objects. They blame their adoptive parents for causing their anger, and they blame toys for breaking. They blame things that could not possibly be responsible for anything!

Most often, children or adolescents who engage in projecting blame are those who have not yet development a conscience. These same children are adept at engaging others in a superficial manner; thus therapists, teachers, and outsiders to the family feel that these children are each to be around, and that they are truly misunderstood by those who should know them best – their parents

Calling the Bluff

These children feign “poor me,” and many professionals are quick to endorse their helplessness and lack of social competence. This victim stance is rarely accurate, and while the young con artists are initially satisfied with their success at hooding yet another adult they ultimately hold him in contempt for “being so stupid.” Many therapists have fallen into this category, and will be of little help to the child and his family if they continue to blame the parents or the family system for the child’s difficulties. Character-disturbed children and adolescents are highly skilled in engaging the therapist, when it should be the other way around.

It is an interesting dichotomy that the same therapists who are easily taken in by disturbed children find it difficult to work with the parents. Since their efforts are focused on helping the parents understand and tolerate the child, the implied – and sometimes direct – message is that the problem is one of parenting. When parents are influenced to feel that their own issues are to blame, they may assume the “I need to change” role. Even when they objectively know that they were perfectly functional prior to becoming adoptive parents, they may be seduced into identifying themselves as the ones that should change. When their thinking no longer matches their experiences, they feel crazy.

Many parents with whom we have worked describe years of non-productive therapy. At the suggestion of therapists whose empathy focused solely on the child, they kept charts of chores, doled out rewards and stickers, and imposed money fines. They compromised their values, altered their expectations, and skewed their rules. They were therapeutically robbed of their parenting roles, resulting in an unexpected shift of power from them to their troubled child. Once this occurred, there was little reason for their child to change.

After many failed attempts at therapy, adoptive parents frequently become defensive, guarded, and overly controlling in their relationships with therapists. Once this happens, the parents are likely to look as if they are, indeed, the ones who need help. We often ask parents, “Did you feel and act this crazy before you adopted Bobby?” When we approach them from a humorously empathic point of view, we generally get a response like, “Finally, we’ve found someone who understands!”

Providing therapeutic support to adoptive parents services two important purposes. First, it helps to counteract years of minimization and disbelief by mental health professionals, teachers, social workers and extended family members. Second, when parents feel supported, they are able to receive, process, and utilize the information they receive from the therapist. They will listen to an ally differently from someone who is blaming them, and are open to making an necessary changes.

We are always clear with our clients about one issue; adoptive parents of previously abused children are not responsible for the problems these children have, but they are responsible for doing what they can to help alleviate them. While we don’t blame adoptive parents, we do expect them to assume a role that is strong, committed, resilient and persevering.

Medication

A common question that frequently arises during therapy is whether or not medications should be used. Some parents summarily reject information about medication with the common arguments, “I don’t want my child to use drugs… I’m not much of a medicine person… I don’t even like to give my child aspirin.” However, the fact remains that there are mental disorders that are clearly biological and respond well to appropriate medication. It would be as foolish to ignore the role of prescription drugs for some children and adolescents as it would be to ignore the use of insulin for diabetes.

Parents need to rely on the healthcare professionals with whom they are working for guidance and expertise. In addition, the behavior of a child on medication should be monitored carefully. We have seen dramatic improvements in those on medication – we have witnessed those who experience little or no change – we have even seen children who exhibit worse behavior after taking medication. Parents should never attempt to alter dosages without first consulting the prescribing physician. Such alterations are unhelpful – at the very least – and can be outright harmful. Medication probably serves its most beneficial purpose when used in combination with supportive services and appropriate therapy.

Parents Role in Therapy

While we have consistently stated that we as therapists support parents, we want to make it clear that this support is not carte blanche. Of course it is the parents’ right and responsibility to call the shots in their families, but is our responsibility to help them make appropriate changes in their interactions with their child that coincide with our therapeutic work with the child.

We are constantly amazed at the reports we hear about therapists who treat children without informing the parents of what happens in therapy. The parents of our young clients are always involved – either by their presence in the treatment room or the observational room. While we have high regard for the confidential nature of some therapy, we firmly believe that the parents of character-disturbed children must be aware of what we are doing. We are honest with the child, and our openness has always proved effective. The children we’ve worked with respond well to a contract that states, “Your parents are important people in your life. Because we believe they are the best people to help you, we want them to know everything that goes on in our work. There are no secrets here, and there will be no secrets about what goes on at home.

This would not be the prescribed treatment contract with a high functioning adolescent who is working through typical adolescent issues such as identity or dependence versus independence conflicts. Just as the treatment itself must be differentially developed, so must the treatment contract.

Most parents whose children have developmental delays and attachment issues – both of which are manifested through significant behavioral problems – become much too serious about everything. They become the child’s opposite; he assumes that nothing is serious. They allow themselves no levity. They take nothing in stride. Instead, even small issues become major issues in their eyes. Their problems and miseries lead to the loss of support of family and friends, and they drift in a sea of isolation.

Like all of us, the adoptive parents have unresolved psychological issues. Since hurt children seem to have a “button-locating radar,” their parents’ issues are generally targeted for exposure, aggravation and agitation. If there’s a button that can be pushed, these children will find it. And once they zero in on it, they push mercilessly.

Every day spent with a disturbed child heightens parents’ awareness of their own issues. Most often, their unresolved struggles are reduced to power-and-control battles with their child. An once the parents are engaged in a battle initiated by the child, they have a difficult time pulling out.

Treatment efforts must therefore be focused on at least two dimensions. First, the parents’ issues need to be explored and resolved. Simultaneously, they must be given the practical strategies and tools for correcting the emotional imbalance in their homes. As a result, the therapist often assumes a multi-dimensional role with the parents, serving as mentor, advisor, psycho-educator, supporter, confronter and guide.

We most often work with parents as part of a comprehensive team – comprised of the social worker, adoption placement worker, and referring therapist. This treatment team must work closely together if the hurt child is to grow and make the changes that may be necessary for him to stay in his adoptive home.

The team process included a complete assessment, involving a structured, written autobiography by each parent; a marital assessment for couples or an individual one for single parents; and a family assessment, done in conjunction with the child’s assessment.

It is imperative for parents to take breaks from therapy, school problems, court problems, and any other unpleasant issues that are part of the package of raising a difficult child. When they take good care of themselves, they continue to grow and develop. They become stronger. More comfortable. And they can laugh at things that used to send them rushing to the therapist. They gain an awareness that there are more good times than bad at home, and that awareness is a source of pure job.

There is no denying the excitement we feel each time we see parents change from reactive to proactive. It is precisely at this point that we know significant progress is in the making. The child has begun to grow, and the parents are just far enough ahead of him to encourage and celebrate his ongoing journey.

About Gregory C. Keck and Regina M. Kupecky

Gregory C. Keck is the founder of the Attachment and Bonding Center of Ohio, which specializes in treating children who have experienced developmental interruptions. He and his staff also treat individuals and families who are experiencing a variety of problems in the areas of adoption, attachment, substance abuse, sexual abuse and adolescent difficulties.

Regina M. Kupecky has worked in the adoption area for over 25 years. She currently works with children with attachment issues at The Attachment and Bonding Center of Ohio.

Reprinted From Paradigm Magazine Winter 1999.

Dr. Keck and Ms. Kupecky co-authored Adopting The Hurt Child Pinon Press Colorado 1995

and Parenting The Hurt Child Pinon Press Colorado 2002.